Paul Otellini's Intel: Can the Company That Built the Future Survive It?

As the CEO steps down, he leaves the Intel machine poised to take on the swarming ecosystem of competitors who make smartphone chips.

Forty-five years after Intel was founded by Silicon Valley legends Gordon Moore and Bob Noyce, it is the world's leading semiconductor company. While almost every similar company -- and there used to be many -- has disappeared or withered away, Intel has thrived through the rise of Microsoft, the Internet boom and the Internet bust, the resurgence of Apple, the laptop explosion that eroded the desktop market, and the wholesale restructuring of the semiconductor industry.

For 40 of those years, a timespan that saw computing go from curiosity to ubiquity, Paul Otellini has been at Intel. He's been CEO of the company for the last eight years, but close to the levers of power since he became then-CEO Andy Grove's de facto chief of staff in 1989. Today is Otellini's last day at Intel. As soon as he steps down at a company shareholder meeting, Brian Krzanich, who has been with the company since 1982, will move up from COO to become Intel's sixth CEO.

It's almost certain that the chorus of goodbyes for Otellini will underestimate his accomplishments as the head of the world's foremost chipmaker. He's a company man who is not much of a rhetorician, and the last few quarters of declining revenue and income have brought out detractors. They'll say Otellini did not get Intel's chips into smartphones and tablets, leaving the company locked out of computing's fastest growing market. They'll say Intel's risky, capital-intensive, vertically integrated business model doesn't belong in the new semiconductor industry, and that the loose coalition built around ARM's phone-friendly chip architecture have bypassed the once-invincible Intel along with its old WinTel friends, Microsoft, Dell, and HP.

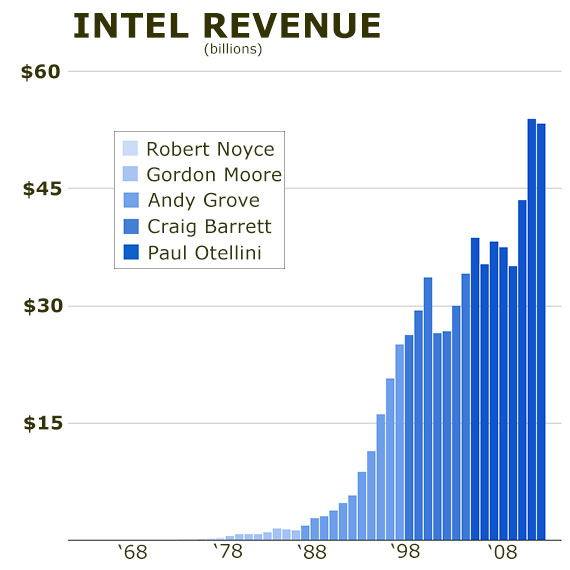

And yet, consider the case for Otellini. Intel generated more revenue during his eight-year tenure as CEO than it did during the rest of the company's 45-year history. If it weren't for the Internet bubble-inflated earnings of the year 2000, Otellini would have presided over the generation of greater profits than his predecessors combined as well. As it is, the company machinery under him spun off $66 billion in profit (i.e. net income), as compared with the $68 billion posted by his predecessors. The $11 billion Intel earned in 2012 easily beats the sum total ($9.5) posted by Qualcomm ($6.1), Texas Instruments ($1.8), Broadcom ($0.72), Nvidia ($0.56), and Marvel ($0.31), not to mention its old rival AMD, which lost more than a billion dollars.

"By all accounts, the company has been incredibly successful during his tenure on the things that made them Intel," said Stacy Rasgon, a senior analyst who covers the semiconductor industry at Sanford C. Bernstein. "Tuning the machine that is Intel happened very well under his watch. They've grown revenues a ton and margins are higher than they used to be."

Even Otellini's natural rival, former AMD CEO Hector Ruiz, had to agree that Intel's CEO "was more successful than people give him credit for."

But, oh, what could have been! Even Otellini betrayed a profound sense of disappointment over a decision he made about a then-unreleased product that became the iPhone. Shortly after winning Apple's Mac business, he decided against doing what it took to be the chip in Apple's paradigm-shifting product.

"We ended up not winning it or passing on it, depending on how you want to view it. And the world would have been a lot different if we'd done it," Otellini told me in a two-hour conversation during his last month at Intel. "The thing you have to remember is that this was before the iPhone was introduced and no one knew what the iPhone would do... At the end of the day, there was a chip that they were interested in that they wanted to pay a certain price for and not a nickel more and that price was below our forecasted cost. I couldn't see it. It wasn't one of these things you can make up on volume. And in hindsight, the forecasted cost was wrong and the volume was 100x what anyone thought."

It was the only moment I heard regret slip into Otellini's voice during the several hours of conversations I had with him. "The lesson I took away from that was, while we like to speak with data around here, so many times in my career I've ended up making decisions with my gut, and I should have followed my gut," he said. "My gut told me to say yes."

In person, Otellini is forthright and charming. For a lifelong business guy, his affect is educator, not salesman. He is the kind of guy who would recommend that a junior colleague read a book like Scale and Scope, a 780-page history of industrial capitalism. To his credit, he fired back responses to nearly all my questions about his tenure, company, and industry at a dinner during CES in Las Vegas and later at Intel's headquarters. And when he wasn't going to answer, he didn't duck, but repelled: "I'm not going to talk about that."

On stage, however, during the heavily produced keynote talks CEOs are now required to give, Otellini's persona and company do not inspire legions of cheering fans. When he steps on stage, there is no Jobsian swell of emotion, no one screams out, "We love you, Paul!" And yet, this is the outfit that pushes the leading edge of chip innovation. They are the keepers of (Gordon) Moore's Law, ensuring that the number of transistors on an integrated circuit continues to double every couple years or so. If Otellini's CV is lacking a driverless car project or rocketship company, it may be because the technical challenges Intel faces require a different kind of corporation and leader.

"He's super low-key guy. He's not a Steve Jobs. He's not a Bill Gates. But his contribution has been just as big," said the new president of Intel, Renee James, who has worked with Otellini for 15 years.

His management secret was his own exemplary drive, discipline, and humility. He came in early, worked hard, and demanded excellence of himself. "He didn't yell and scream. He never dictated. He never asked me to come in on a Sunday. He never asked me to stay late on a Friday. But he had this way of getting you to rise to the occasion," said Navin Shenoy, who served as Otellini's chief-of-staff from 2004 to 2007. "He'd challenge you to do something that we'd all be proud of."

Peter Thiel might complain that the Valley hasn't invented rocket packs and flying car because investors and entrepreneurs have been focused on frivolous nonsense. But Paul Otellini's Intel spent $19.5 billion on R&D during 2011 and 2012. That's $8 billion more than Google. And a substantial amount of Intel's innovation comes from its manufacturing operations, and Intel spent another $20 billion building factories during the last two years. That's nearly $40 billion dedicated to bringing new products into being in just two years! These investments have continued because of Otellini's unshakeable faith that eventually, as he told me, "At the end of the day, the best transistors win, no matter what you're building, a server or a phone." That's always the strategy. That's always the solution.

Intel's kind of business and Otellini's brand of competent, quiet management are not in fashion in Silicon Valley right now. And yet, almost no one has can claim the Valley more than Otellini. Every day for four decades -- in a career that spans the entirety of the PC era -- Intel's Santa Clara headquarters have been the center of his working world.

As we stood outside Otellini's corner cubicle, marked by a makeshift waiting room with a television, a couple of display cases, and a plucky plant, I asked him to reflect on what the end might feel like. "It is strange. I've been pinning this badge on every day for 40 years," he said. "But I won't miss the commute from San Francisco." After making thousands of trips down 101 and racking up 1.2 million miles on United through hundreds of trips around the world, he seemed ready to stop going.

The Many Computer Revolutions

Despite the $53 billion in revenue and all the company's technical and business successes, the question on many a commentator's mind is, Can Intel thrive in the tablet and smartphone world the way it did during the standard PC era?

The industry changes ushered in by the surge in these flat-glass computing devices can be seen two ways. Intel's James prefers to see the continuities with Intel's existing business. "Everyone wants the tablet to be some mysterious thing that's killing the PC. What do you think the tablet really is? A PC," she said. "A PC by any other name is still a personal computer. If it does general purpose computing with multiple applications, it's a PC." Sure, she admitted, tablets are a "form factor and user modality change," but tablets are still "a general purpose computer."

On the other hand, the industry changes that have surrounded the great tablet upheaval have been substantial. Consumer dollars are flowing to different places. Instead of Microsoft's operating system dominating, Apple and Google's do. The old-line PC makers have struggled, while relative upstarts such as Samsung and Amazon have pushed millions of units.

The chip challenges are different as well. Rather than optimizing for the maximum computational power of a device, it's energy efficiency that's most important. How much performance can a processor deliver per watt of power it sucks from a too-small battery?

The semiconductor industry itself has seen perhaps even larger changes. In the early days of Silicon Valley, chipmakers had their foundries right there in the Valley, hence the name. During the 1980s, Japanese chipmakers battled American ones, beating them badly until Intel turned the tide in the latter half of the decade. The factories moved out of the valley to places like domesticallyChandler, Arizona and Folsom, California, as well as to Asia, mostly Taiwan.

Meanwhile, each generation of chips got technically more challenging and the foundries required to build them got more expensive. Chipmakers needed to sell massive amounts of chips in order to make up the huge capital equipment costs. The industry became cruelly cyclical, booming and busting with a regularity that defied managerial skill. For all those reasons and more, during the last twenty years, the chipmaking industry has been consolidating. Almost all semiconductor companies are now "fabless," choosing to outsource the production of their silicon to Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), United Microelectronics Corporation (UMC), or GlobalFoundries, a venture backed by the United Arab Emirates. The new fabless chip designers don't have to build plants, which allows them to have more stable businesses, but they lose the ability to gain competitive advantage by tweaking production lines. The transition to this state of affairs killed off many companies and allowed others to thrive.

Add it all up and there are only a few chipmakers left standing. The aforementioned contract manufacturers like TSMC, Samsung, and, of course, Intel.

These two structural trends at the consumer and industry levels intersect at a formerly obscure British company called ARM Holdings. Originally founded as a partnership between Acorn Computers (remember them?), VLSI (remember them?), and Apple, ARM now just creates and licenses the chip architectures that other companies tweak and have manufactured. In a sense, they sell a chip "starter kit" that companies like Apple, Qualcomm, Broadcom, Marvel, and Nvidia build upon to create their own products.

Chips based on the ARM intellectual property are generally not as high-performance as Intel's, but they're fantastically energy efficient. While ARM did make chips for Apple's ill-fated Newton device, in the early 2000s, ARM became the dominant architecture supplier to the so-called "embedded" market. These chips are not general computing devices, but have specific jobs in (for example) cars, hard drives, and factories. This specialization is also one of the reasons that ARM chips are cheap. An Intel microprocessor could sell for $100. ARM-based chips might sell for $10, and often less than a dollar. In the first quarter of this year, 2.6 billion chips using ARM's architecture were shipped.

The two key attributes of ARM's architecture -- energy efficiency and low cost -- developed before cell phone phones, but they were exactly what mobile designers were looking for. As the smartphone market exploded, so did ARM's share price as investors realized what a key node ARM had become in the burgeoning computer-on-glass phone and tablet market.

For companies who are trying to decide whether to go with Intel or an ARM-licensee, it's a bit like being asked whether you'd rather deal with Switzerland or the Aztec empire. "With ARM, when you are tired of Qualcomm you can go to NVIDIA or another company," Linley Gwennap, the boss of the Linley Group, a research firm, told The Economist last year. "But in Intel's case, there's nobody else on its team."

ARM-based designs are now found in more than 95 percent of smartphones. ARM may not be dominant in the way Intel is dominant in PCs, but the system it underpins is.

Simon Segars is the man who will have to deal with the fallout from all of ARM's successes. He begins as the new CEO of the company on July 1. I met him after he spoke on a panel about "multi-industry business ecosystems" at the Parc 55 hotel in the heart of San Francisco. He was tall and genial, happy to patiently and thoroughly explain why ARM had found itself in possession of so many friends and so much good fortune.

"I can genuinely say that our approach is to work within an ecosystem that is a healthy ecosystem. By that I mean the people in it are making money from what they do," he said. "We get questions on a regular basis, Why don't you quadruple your royalty rates? Because you're so strong, what are you customers going to do? We could do that and we could probably enjoy some more revenue for some time, but our customers would go off and do something else or have less healthy businesses. If we tried to extract lots of money out of the ecosystem, we'd have less companies supporting the ARM architecture and that would limit where it could go."

ARM is a company that finds itself in the right place at the right time with a philosophy of innovation that lots of companies want to believe in.

"Through the '90s and early 2000s, we saw an explosion in the number of people who could build a chip. That led to a lot of innovation and all the electronic devices that we see today," Segars said. "The role we've played is providing this core building block, this microprocessor, that many of these devices require. We've provided that in a very cost-effective way to anybody who wanted it. And that's allowed people to put intelligence into devices that they couldn't have afforded to do because they would have had to do it all themselves."

The Mobile Mystery: What Did Otellini See and When Did He See It?

Many of the structural changes that occurred in these industries now seem predictable. It feels like somebody else could have positioned Intel differently to take advantage of these trends. At the very least, Otellini should have seen where the changes were leading the silicon world.

And the thing is, he did. He just wasn't able to get the Intel machine turning fast enough. "The explosion of low-end devices, we kinda saw as a company and for a variety of reasons weren't able to get our arms around it early enough," he admitted.

It was Otellini, after all, who had made the call to start developing the very successful low-power Atom processor for mobile computing applications. And it was Otellini, who upon ascending to the throne, drew a diagram that I'll call the Otellini Corollary to Moore's Law at the company's annual Strategic Long Range Planning Process meeting, or SLRP. He duplicated it for me in an appropriately anonymous Intel conference room, calling it half-jokingly "the history of the computer industry in one chart."

On the Y-axis, we have the number of units sold in a year. On the X-axis, we have the price of the device, beginning with the $10,000 IBM PC at the far left and extending to $100 on the far right. Then, he drew a diagonal line bisecting the axes. As Otellini sketched, he talked through the movements represented in the chart. "By the time the price got to $1000, sort of in the mid-90s, the industry got to 100 million units a year," he said, circling the $1k. "And as PCs continued to come down in price, they got to be an average price of 600 or 700 dollars and we got up to 300 million units." He traced the line up to his diagonal line and drew an arrow pointing to a dot on the line. "You are here," he said. "I don't mean just phones, but mainstream computing is a billion units at $100. That's where we're headed."

"What I told our guys is that we rode all the way up through here, but what we needed to do was very different to get to [a billion units]... You have to be able to build chips for $10 and sell a lot of them."

"This is what I had to draw to get Intel to start thinking about ultracheap," Otellini concluded.

"How well do you think Intel is thinking about ultracheap?" I asked.

"Oh they got it now," he said, to the laughter of the press relations crew with us. "I did this in '05, so it's [been more than] seven years now. They got it as of about two years ago. Everybody in the company has got it now, but it took a while to move the machine."

It took a while to move the machine. The problem, really, was that Intel's x86 chip architecture could not rival the performance per watt of power that designs licensed from ARM based on RISC architecture could provide. Intel was always the undisputed champion of performance, but its chips sucked up too much power. In fact, it was only this month that Intel revealed chips that seem like they'll be able to beat the ARM licensees on the key metrics.

No one can quite understand why it's taken so long. "I think Intel is still suffering with the inability of this very fine company to enter a new major segment that changes the game," Magnus Hyde, former head of TSMC North America told me. "That's been a problem before Paul, been a problem during Paul, and will probably be a problem going forward. They have all the things they need on the paper: the know-how, the customers, the cash to take over whatever they need. But somehow a little piece is missing."

"This is a company with 100,000 employees with a 40-year legacy. They are unbelievably good at what they do. No one can touch them," said Rasgon, the analyst. "There is a certain degree of arrogance that goes align with that."

"As CEO, that's your job: steer [the ship]," he continued. "It doesn't necessary mean [Otellini had] a failure of vision, but he couldn't get the ship to turn."

Ruiz, who led AMD's last battle with Intel while he was CEO from 2002 to 2008, told me he thought Intel's mobile progress had been slowed by their concentration on his company. "The focus the company has had for the past three decades on squashing AMD caused them to lose sight of the important trends towards mobility and low power," he said. "They should have focused more on their customers and the future than on trying to outdo AMD."

Some people seem to think someone else could have done better. And it's nice to believe in the transformative leader. Call it the Fire-the-Coach Fallacy. Sometimes, installing a new leader of an organization leads to better performance. But far more often, as some simple Freakonomics blogpost would tell you, we overestimate the importance of changing the coach or the CEO. It's not that CEOs are not important, but the preexisting conditions within and surrounding a company are just more important.

Unlike a lot of leaders, Otellini seems aware of this fact. "Intel's culture is blessedly not the culture of a CEO, nor has it ever been," he told me. "It's the Intel culture."

Otellini, of course, knew the Intel culture well. It had formed the substrate of his entire career. Starting out in finance in 1974, he'd worked his way up the chain on the business side of the operation, eventually landing the key gig of managing Intel's IBM account in 1983. It was right before Intel abandoned the memory business. He'd worked closely with Andy Grove, watching how he processed information, managed, and made decisions. He'd spent two years in the executive suite with Craig Barrett, watching him steer Intel in the rocky days after the Internet bust.

The Intel culture has been remarkably successful, of course. But it has also shown a resistance to change. It has managed to successfully surf massive transitions like getting out of the memory business in 1985 to focus on microprocessors and retaining a leading position in the move from desktop processors to laptops, but the same focus and scale that make Intel so powerful also prevent it from changing tacks quickly. If you've got 4,000 PhDs and 96,000 other people working for you, it's hard to turn on a dime.

Perhaps, though, the transformation that Otellini began in 2005 will finally be complete during Brian Krzanich's tenure. Intel's technical lead, perfectionism, and scale will create amazing chips at prices that cause phone and tablet makers to give up their commitments to the ARM ecosystem.

"They already have products in the marketplace that are competitive and I would not be surprised if they had best-in-class products in a few years," Rasgon said. "What they are doing on the [manufacturing] process has really driven that."

Otellini sees an analogy to the current situation in Intel's performance with Centrino laptop chips. "Intel made the big bet. [Chief Product Officer] Dadi [Perlmutter] and I made the big bet in 2001 to bet on mobile. This was when the desktop was 80 percent of all PCs, maybe 90 percent, and unabated growth and notebooks were luggables," Otellini said. "And we thought that there was an argument about what a computer could be and that led to what would become Centrino."

Centrino chips won over Apple's Steve Jobs because the silicon was so good they could not be ignored. "The head-to-head of comparison of an Intel based notebook and an Apple notebook were night and day in terms of performance, battery life, etc," he said. "That's what got their attention."

And if Apple -- so notoriously anti-Intel that a 1996 Mac commercial showed a burning Intel mascot -- could come to love Intel processors, couldn't all the current ARM licensees see the blue Intel light?

A Battle of Innovation Cultures: The Lab Vs. The Ecosystem

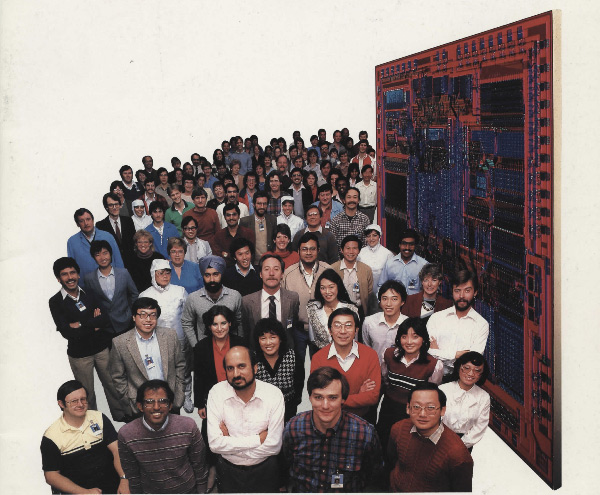

Silicon Valley has been, rightly or wrongly, synonymous with innovation for four decades. Now, it's as much a notion as a place. When Paul Otellini joined Intel in 1974, a year of bloodletting at the company that also saw two of its future CEOs hired (Otellini and his predecessor Craig Barrett), the peninsula south of San Francisco and the Santa Clara Valley had merged in the American mind into the crucible for the future. Though Intel would only make $20 million that year, it was clear that these chips, and their tendency to get cheaper so quickly, were a new force unto the world. The whole enterprise was shaped by individual humans, structured by capitalism, and aided by Cold War R&D money, but the effects of all this memory and computation, its exponentiality, were hard to predict. A story led the New York Times business section a couple years later with the banner headline, "Revolution in Silicon Valley." The subheadline read, "'The basic thing that drives technology is the desire to make money,' says one executive. Now, where can they use the technology?"

Think of that as a kind of ur-mainstream media Silicon Valley story. It's got all the elements: an early reference to the orchards that used to exist, "low-slung" buildings as the unlikely seat of revolution, hot consumer products, hypercompetitive industries, massive innovation, great men, something like a formulation of Moore's Law, and the exceptionalist sense that this could only happen in this one place in California.

There are two conflicting narratives about all this Silicon Valley innovation. On the one hand, there is the notion that Silicon Valley is an ecosystem of entrepreneurs and inventors, financiers and researchers. Companies can break up and reassemble. Spinoffs can pop out of larger corporations. Startups can disrupt whole industries. Competitors can cooperate and then compete and then cooperate. And when you add up all these risk-taking, failure-forgiving people, the sum is greater than the parts. Fundamental to this notion is the idea that innovation happens best in networks of firms and individuals, in an ecosystem (a word that itself gained credence thanks, in part, to Stanford ecologist Paul Ehrlich in the late 1960s).

On the other hand, we have Intel. Intel structured and thought of itself like a research laboratory, according to long-time Silicon Valley journalist Michael S. Malone, in his 1985 book, The Big Score. "The image of a giant research team is important to understanding the corporate philosophy Intel developed for itself," Malone wrote. "On a research team, everybody is an equal, from the project director right down to the person who cleans the floors: each contributes his or her expertise toward achieving the final goal of a finished successful product."

Malone went on that the culture of Intel was not that of a bunch of loosey-goosey risk takers, but true believers, almost robotic in their dedication to Intel's goals. "Intel was in many ways a camp for bright young people with unlimited energy and limited perspective," he continued. "That's one of the reasons Intel recruited most of its new hires right out of college: they didn't want the kids polluted by corporate life... There was also the belief, the infinite, heartrending belief most often found in young people, that the organization to which they've attached themselves is the greatest of its kind in the world; the conviction they are part of a team of like-minded souls pushing back the powers of darkness in the name of all mankind."

This is a very different vision of innovation. This is an army of people tightly coordinated, highly organized, and hardened by faith. It was this side that competitors and suppliers have long encountered and complained about (sometimes appealing to the regulatory authorities).

"They are tough to deal with. I know some of the executives privately and they say, 'We're not really nice people to deal with.' They admit it. And it's true," Magnus Hyde, former head of Taiwan Semiconductor North America, told me. "They are really nasty when you get into negotiations."

And as for this whole "failure's cool!" mantra that seems to re-echo around Silicon Valley, Intel's Andy Grove enshrined what he called "creative confrontation," which encouraged and rewarded people to get after each other for flagging performance or mistakes.

Taken as a whole, Intel is a self-contained research, development, and deployment machine. That is not an ecosystem. Though obviously Intel has many partners with whom it makes money and has good relationships, on the leading edge of innovation, Intel goes it alone.

Time and again, this strategy has worked as almost all of their competitors have fallen by the wayside. Intel is the only chip company in the world that's been able to hang on to its vertically integrated business model. "They have these methods, these Intel methods, that have worked very well for them," Hyde said.

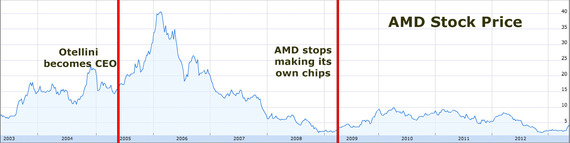

The way Otellini vanquished AMD is a classic example of the Intel way. AMD had always played Brooklyn to Intel's Manhattan. Otellini himself had offers from both companies coming out of business school, and the competition remained fierce all the way until he took the reins. AMD was resurgent then. They had beat Intel to market with excellent 64-bit chips that were perceived to provide more performance for less money than Intel's processors. AMD's stock was on a climb that would take it to dizzying heights. By the end of 2008, Intel had destroyed AMD's momentum and sent the company into a tailspin. Finally, in early 2009, AMD spun out its fabrication facilities, exiting the chipmaking game. It was TKO in the longest-running bout in Silicon Valley. "They buried AMD," Rasgon put it bluntly.

Of course, there were several ugly court battles about Intel's hardball tactics in keeping AMD out of more machines. Intel eventually paid AMD $1.25 billion to settle the case in late 2009.

What's clear is that when Intel has a single competitor to focus on, they are hard to beat. "The thing about Intel is that we always come back," Otellini told me. "We put resources on it. We get focused. And watch out." They outinnovate, outmanufacture, and outcompete any company that comes into their targets.

Which brings us back to the question of mobile, the space that has eluded Intel for a decade. What's fascinating is that it's a battle between Intel and a swarm of companies licensing chip designs from a relatively small IP company, ARM. Intel has bulk and strength, but they've come up against that other model of innovation: the ecosystem. It's two ideas about how Silicon Valley works locked in combat. If you're the swarm, with Qualcomm as the queen bee, the question is: How do you hold the coalition together?

If you're Intel, which fly do you fire the shotgun at? Not ARM, that's for sure.

"ARM is an architecture. It's a licensing company," Otellini said. "If I wanted to compete with ARM, I'd say let's license Intel architecture out to anyone that wants it and have at it and we'll make our money on royalties. And we'd be about a third the size of the company."

"It's important for me, as the CEO, that I tell our employees who it is that we have to compete with and who we're focused on, and I don't want them focused on ARM. I want them focused on Qualcomm or Nvidia or TI," he continued. "Or if someone like Apple is using ARM to build a phone chip, I want our guys focused on building the best chip for Apple, so they want to buy our stuff."

I asked ARM's Segars about what I'd heard from Otellini, namely that Intel would beat the individual members of his coalition because they make the best transistors, and that would ultimately carry the day.

"There is a long track record of Intel investing very heavily on the leading edge of technology and implementing innovations of process technologies ahead of everybody else. That is a statement of fact and nobody would dispute that," Segars responded. "The transistors are, of course, important. The way in which the transistors are used is very important and really what the explosion of the technology space over the last couple of decades has shown is that there is a need to innovate and you can't focus innovation in just one company. If all the world's chips came from one vendor, whether it's Intel or anybody else, naturally that's going to limit innovation because there are only so many people and there will be a philosophy that's followed."

But Otellini, or Krzanich, can't focus Intel on ARM's "intangible" rhetoric. The questions industry watchers should be asking, Otellini said, are these ones: "Do you think Intel can beat Qualcomm? Do you think Intel can beat Nvidia? Do you think Intel can compete with Samsung?"

The answer might be yes, Intel can compete with each one, but maybe not with them all.